Credit Suisse and UBS finally move on coal – but they’re still in climate cloud cuckoo land

Two years on from Bank of America and Crédit Agricole making their first policy moves to distance themselves from the coal mining sector, we can now count 22 western banks which have followed them in the lead up to, and beyond, the Paris COP21 meeting in December 2015. The Swiss members of this pack, the global giants Credit Suisse and UBS, last month published the latest updates to their coal sector policies.

Disappointingly, however, both banks have ducked their chance with these policy reviews and find themselves still lagging behind many of their European peers which have already fully called it a day on direct financing of new coal mines and plants worldwide. And Credit Suisse also seems to be on an alarming coal finance expedition in Turkey.

UBS was in fact the first major international bank to move right after COP21 when, as BankTrack covered here, it updated its ‘Environmental and Social Risk Policy Framework’ on coal in December 2015. The major let-down then was that UBS chose not to exclude financing for coal mines or coal plants, and that the wording used in the policy update was unique, in a bad way.

World leaders may have been in climate unison with the emergence of the Paris Agreement, yet UBS saw fit to do no more than ‘continue to significantly limit its lending and capital raising engagement with coal mining companies’ – and this despite the bank occupying fifth place among European banks in last year’s Fossil Fuels Finance Report Card as a result of dishing out more than $1 billion in financing to coal mining companies between 2013 and 2015.

And it was even more difficult to expect anything concrete or ambitious to result from further lukewarm policy language deployed by UBS, this time related to coal power – it lamely pledged to exclude from financing only ‘companies operating coal-fired power plants who (do not) adhere to strict internationally recognized greenhouse gas emission standards’. In turn, this effectively rendered useless its other exclusion criteria of companies who do not ‘have a strategy in place to reduce coal dependency’.

With its new updated coal policy published last month, UBS has rectified only one of these shortcomings with a commitment to end financing for new coal-fired power plant projects in high-income OECD countries, with coal power support continuing elsewhere in the world but restricted to high-efficiency, low-emissions (HELE) coal technologies. This could have been considered a good move a few years ago, but is a huge missed opportunity now in 2017 given that eight other big European banks have totally excluded such financing worldwide.

The new coal policy also comes hot on the heels of a new paper on banks’ human rights responsibilities from the Thun Group, a group of banks convened by UBS, with Credit Suisse also a member. This latest Thun Group offering has already been slammed by Professor John Ruggie, the architect of the UN’s Guiding Principles on business and human rights, as misconstruing core elements of these Principles. The paper declared that banks cannot contribute to human rights impacts through their finance, and therefore have no responsibility to address such impacts. Ruggie, and other experts, disagree. With coal projects frequently leading to community conflict, this adds to the sense that Swiss banks are not at the vanguard of sustainable finance right now.

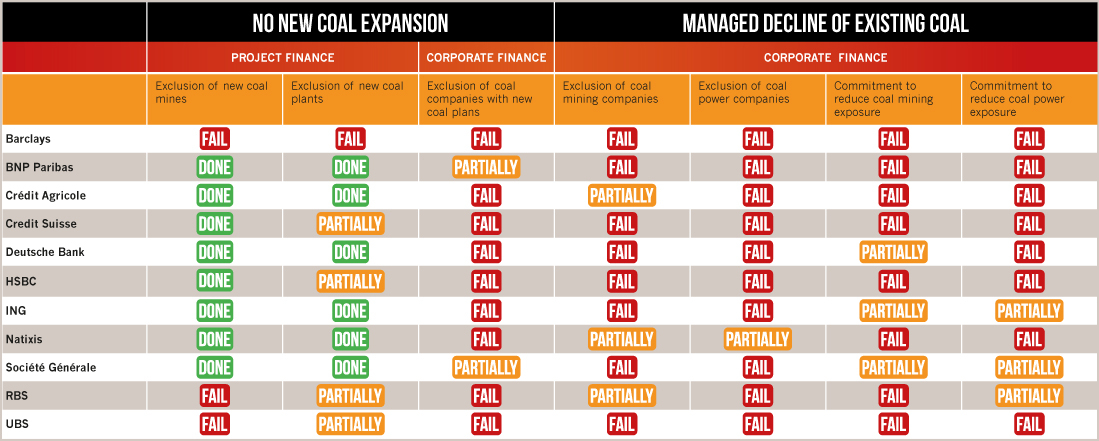

CLICK HERE TO SEE TABLE IN FULL SIZE

Alas Credit Suisse has also now failed to pull up the Swiss banking sector’s coal policy socks and make up for the UBS policy misfire.

Since COP21, Credit Suisse had only moved on the exclusion of mountaintop removal companies last year at its AGM, and nothing more. However, also published in March, the bank’s updated ‘Summary of Mining Policy’ does make some strides forward: for one thing, Credit Suisse is calling a halt to its financing of new greenfield thermal coal mines. Regarding coal power, a new ‘Summary of Power Generation Guidelines’ was also published and matches the exclusions announced by UBS: no further financing of new coal power plants in high-income OECD countries, with such investments in the rest of the world again restricted to new ultra-supercritical coal plants. Once more, though, the lack of climate ambition is palpable.

Moreover, and despite its alarming positions in our latest rankings – for 2013-2015 the third-placed European bank for coal mining company support with almost $2 billion dollars disbursed, and fifth-placed with more than $5 billion for coal power – Credit Suisse has contrived not to introduce any sector level exclusion criteria or reduction commitment in these revised policies.

And even on the provisions for direct coal project exclusions, we are confronted with the same implementation issue as has been encountered in the case of ING’s involvement in the Cirebon 2 coal plant project in Indonesia. Namely, that Credit Suisse has chosen to insert some small print giving it latitude to keep its fingers dirty with coal: ‘an exemption to this provision (new coal mine exclusion) applies to transactions that were already under review when this restriction was introduced in 2016.’

This seems to be precisely the case for the Amasra coal mine project in Turkey, where local groups have reported being approached in February this year by a consultant working for the bank who was conducting due diligence for the project.

This coal mine sits right next to the planned Amasra coal plant, which has been vigorously opposed for 12 years by local communities, part of the Bartın Platformu which consists of 120 non-governmental organisations and various municipalities. This broad platform has held demonstrations and protests to protect the beautiful Black Sea town of Amasra – the ancient part of the town features on UNESCO’s temporary World Heritage list – from the impacts of the project. This has the makings of a full-blown dodgy deal: one for all banks to avoid, and one for what appears to be first-mover Credit Suisse to distance itself from quickly.

Thus Switzerland’s top two banks remain at the back of the pack of European banks, as our coal policy overview table shows above. Credit Suisse and UBS now need to fully exclude the financing of all and any new coal mines and coal plants worldwide, and adopt some stringent exclusion policies at the coal sector level if they want to get out of the coal policy slow lane quickly.

These two policy reviews may have just taken place, but they barely deserve to be described as such. Both banks have the chance to make amends quickly at their respective AGMs over the next couple of weeks – starting with Credit Suisse this coming Friday (April 28).