Swiss banks are lashing out at climate activists rather than taking action. This has to stop.

Claire Hamlett, climate campaigner, claire@banktrack.org

Claire Hamlett, climate campaigner, claire@banktrack.org

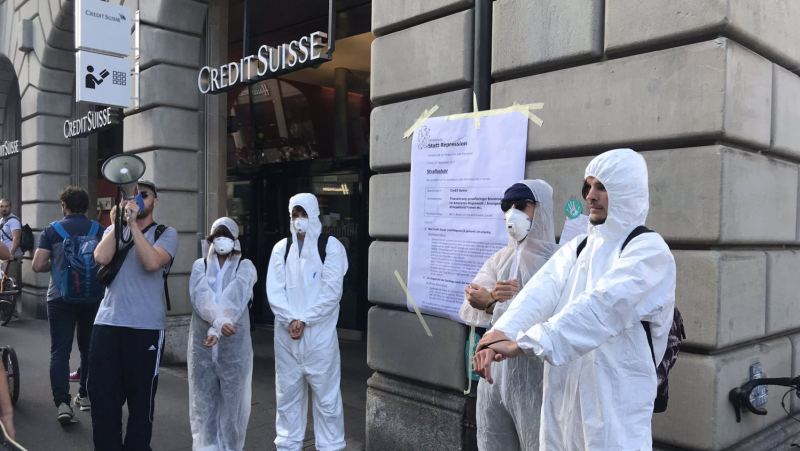

Wearing hazmat suits and with their hands bound, climate activists in Switzerland last week served Credit Suisse with a ‘punishment order’ for funding the climate crisis through its support for the fossil fuel industry. The September 27 action comes after 64 activists were arrested and served their own punishment orders during a blockade of Credit Suisse’s Zurich headquarters in July, with a further 19 arrested in Basel for a concurrent action outside a branch of UBS.

The punishment order delivered to Credit Suisse was symbolic and has no legal authority, but the ones received by the activists in July certainly do. In Switzerland, a ‘punishment order’ (‘Strafbefehl’ in German) is a conviction for an offence that is considered clearcut and therefore does not need to go to court, such as when a driver is caught speeding, and comes with a fine. The activists from Collective Climate Justice, who blockaded Credit Suisse and UBS in July, using their bodies, tree branches, and a pile of coal, were handed the punishment orders after being swiftly evicted by police in both Zurich and Basel.

But it was the banks themselves that decided to bring further charges against the activists. On the day of the action, a UBS spokesperson said the bank had filed a criminal complaint against the protesters for coercion, trespassing and property damage, while Credit Suisse also filed a criminal complaint for the blockading of the bank’s entrance, which they said affected staff and customers.

By the time of the blockade this summer, Credit Suisse had already shown itself to be intolerant of challenges to its support for fossil fuels. In November 2018, climate activists staged tennis matches in Credit Suisse branches, in reference to tennis player Roger Federer, a Credit Suisse ‘ambassador’. This resulted in arrests and suspended sentences being handed to two dozen activists. The forceful reaction against peaceful protest by Credit Suisse and, now, UBS sets the Swiss banks down an antagonistic path that other banks have so far avoided.

In Europe, several banks have been the target of protests similar to those experienced by Credit Suisse and UBS. In France earlier this year, hundreds of climate activists staged a sit-in at Société Générale headquarters and doused the bank’s logo in oil. Yet the bank did not take legal action. In 2014, pro-Palestine activists occupied and subsequently shut down branches of Barclays in protest against the bank’s investments in companies supplying arms to Israel. Even with this disruption to its day-to-day business, the bank did not press charges.

Until the Swiss actions, bringing charges against activists and campaigners was a tactic deployed by oppressive political regimes and certain fossil fuel companies trying to squash opposition to their projects. Recall the Arctic 30 detained by Russian authorities in 2013, or the racketeering charges, eventually thrown out, against BankTrack, Greenpeace, and Earth First! brought by Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), the company behind the Dakota Access Pipeline. Is this the company that Credit Suisse and UBS want to keep?

The Swiss banks that are now taking the most extreme steps against climate protests in the banking world are also among the worst climate offenders in Europe in terms of finance for fossil fuels. Since the signing of the Paris Agreement, Credit Suisse and UBS have provided more than US$80 billion to the coal, oil, and gas industries between them. UBS has even been increasing its overall contributions to fossil fuel companies year on year since 2016. Credit Suisse ranks as the third biggest banker of fossil fuels in Europe, after Barclays and HSBC.

“The environmentally destructive and human rights-abusing business model of big banks such as Credit Suisse and UBS must not be ignored,” says Frida Kohlmann, the press spokesperson of the Collective Climate Justice. “They are the real criminals.”

Meanwhile, both banks say they support the Paris Climate Agreement; they are both founding signatories of the recently launched Principles for Responsible Banking; they talk about supporting the ‘low-carbon transition’. Yet there is a crucial piece missing from their climate strategies: their financing for fossil fuels, the biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions on the planet. It is not sufficient for banks to increase their financing to renewable energy and other green projects; they must simultaneously enact a rapid decrease of finance flows to the fossil fuel industry.

One activist from Collective Climate Justice who wanted to remain anonymous said: “Credit Suisse and UBS are the main Swiss financial centers responsible for the global climate catastrophe. Although no oil is produced or coal burned here, it is from here that such projects are financed and made possible.”

It is this contradiction between the banks’ words and deeds that activists aimed to highlight in the July blockades. They demand nothing more of the banks than that they act on the commitments they claim to have made to help pursue efforts to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C. Yet instead of doing this, Credit Suisse and UBS have chosen to intimidate and criminalise civilians who publicly pointed out the banks’ own failures. When banks choose this course of action, their stated commitments to fighting climate change ring very hollow indeed.

Additional information on the arrests of activists:

List of incidents during and after Zurich and Basel blockades

Media release from Climate Justice Collective