Dutch bank ING supports controversial pipeline to import gas from authoritarian Azerbaijan

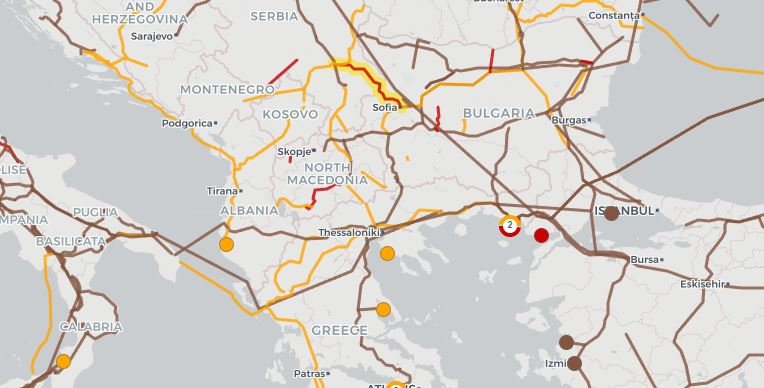

In early February, the Dutch bank ING confirmed a €49 million loan to support the Bulgaria-Serbia Interconnector Gas Pipeline, part of the Southern Gas Corridor pipeline which will bring gas from Azerbaijan, Greece and the Black Sea to Europe. The new Interconnector Pipeline’s capacity is 1.8 billion cubic metres of natural gas per year, meaning it will be responsible for a potential 2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions annually.

The loan comes despite ING’s repeated commitments to reduce its fossil fuel exposure. Last year, the bank announced it will stop funding new upstream oil and gas projects, i.e. those that involve exploration and production. The bank is also part of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance and has set targets to cut its financed emissions.

However, ING’s current policies and emission targets do not prevent it from providing money to midstream projects, which involve transporting or storing fossil fuels - like the Interconnector Pipeline.

The pipeline is listed as an important investment in the EU’s regional plan for the western Balkans. It is an essential part of the Southern Gas Corridor, which is supposed to foster the transition from coal and to fill the gap in energy supply caused by the war in Ukraine. But the pipeline won’t be operational for at least another year, therefore not contributing to solving the current shortages. With the average lifespan of gas pipelines at 50 years, it will instead lock the continent into using dirty fossil fuels instead of renewables.

Moreover, the gas that would flow to Europe through the Interconnector Pipeline would come with a host of social and environmental issues. Europe would source most of its fuel from Azerbaijan, where the ruling regime has built its power on exploiting its gas resources and violently suppressing dissent. The Aliyev family, which has been in charge of the country for three decades, maintains control through a system of fraudulent elections, political violence, and media censorship. According to Human Rights Watch, the Azeri government keeps dozens of opposition politicians, journalists, and activists wrongfully imprisoned.

In 2015, the European Parliament adopted a resolution calling for the suspension of every kind of funding from the EU to the Azeri government. Yet the EU chose to disregard the resolution and ignore blatant human rights abuses by supporting this pipeline. In trying to reduce its energy dependence on Russia, the EU simply chose to swap one tyrant for another.

The impacts of the Southern Gas Corridor extend to the environment as well. Local groups in Italy called attention to the impact of the local stretch of the Corridor, called the Trans Adriatic Pipeline, on their land, where construction will require the removal of thousands of old, rare olive trees. Developers also intend to build a compressor site in the Greek plain of Serres, an area with high earthquake potential. Alongside the Corridor’s proposed route through a flood-prone region of northern Greece, this problem poses a serious threat to the pipeline’s integrity. A broken pipeline would cause severe methane emissions and potential explosions.

Financing the pipeline is also out of line with the Net Zero by 2050 scenario of the International Energy Agency (IEA), which ING uses as the basis for its own reduction targets. According to the IEA, there is no need for new fossil fuel supply in its 1.5 degree-aligned net zero pathway. It also says that “given the rapid decline of fossil fuels, significant investment in new oil and gas pipelines are not needed in the NZE”.

Similarly, in an October 2022 meta-analysis of 1.5C aligned net zero scenarios including the IEA’s, the International Institute for Sustainable Development showed that “there is no room for new fossil import infrastructure in Europe in 1.5°C-aligned gas phase-out pathways.” (p. iv) After the “short-term supply crunch” in 2022 and 2023, which the pipeline will not be able to address, as construction will not be completed until the end of 2023, Europe’s current capacity is sufficient for the projected import needs in the longer term.

ING claims its priority is “to finance and support clients who have ambitions to decarbonise their activities and engage with new ones that will allow us to further steer our portfolio towards net zero targets by 2050.” Financing the Interconnector pipeline goes against this stated priority and is a massive step in the wrong direction.

On 7 March, 26 Dutch charities and small businesses that bank with ING, including relief organisation Cordaid, trade union FNV and social enterprise YB, took out an ad in one of the Netherlands’ top newspapers, calling on the bank to stop financing oil and gas projects. They pointed out that climate change has already ravaged the countries where they work, and that financial institutions must play a key role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Even ING’s own pension fund has decided to divest from fossil fuels in 2022 already, and now excludes companies that derive more than 1% of their revenue from coal, 10% from oil or 50% from gas.

These actions from some of ING’s key stakeholders further emphasise that the next steps are clear: ING should stop financing for infrastructure projects that further lock Europe and the world into dependency on gas, even more so where the gas originates from fraudulent and human rights abusing regimes.