Project – Target

This profile is a priority campaign targetBankTrack, Advocates for Community Alternatives (ACA), Center for Transnational Environmental Accountability (CTEA) & Human Rights Watch

Giulia Barbos, giulia@banktrack.org

Project – Target

This profile is a priority campaign targetBankTrack, Advocates for Community Alternatives (ACA), Center for Transnational Environmental Accountability (CTEA) & Human Rights Watch

Giulia Barbos, giulia@banktrack.org

Why this profile?

Nestled in the forested mountains of Guinea in West Africa, the Simandou iron ore mining project involves the construction of a large open-pit mine, a railway line and a deep-water port. The project risks the displacement of local communities, lost livelihoods, the destruction of critical habitats for endangered species, deforestation, and environmental pollution including greenhouse gas emissions. Communities in every area of the project have already suffered serious impacts to their agricultural and fishing livelihoods, pollution of water sources, and loss of land as a result of unchecked construction activities. Moreover, there are concerns regarding the project's transparency and accountability, as well as the potential for corruption and conflicts of interest.

What must happen

Banks and other financial institutions considering providing direct or indirect finance to this project should ensure its numerous environmental and social impacts and risks are addressed to the satisfaction of local communities. More specifically, communities demand that project developers

- commit to upholding the highest environmental and human rights standards, including those relating to resettlement and land acquisition;

- increase transparency by publishing all project agreements and up to date impact assessments;

- keep communities informed by meaningfully consulting with them on an on-going basis;

- properly account for impacts on climate change and biodiversity; and

- develop an independent grievance mechanism to address community complaints.

Project-affected peoples’ recommendations are set out in more detail by Action Mines in their report on the project here (see page 32, in French).

| Sectors | Iron ore mining, Mining |

| Location |

|

| Status |

Planning

Design

Agreement

Construction

Operation

Closure

Decommission

|

| Website | https://www.riotinto.com/en/operations/projects/simandou |

The Simandou project, located in the Simandou mountain range area in southeastern Guinea, is one of the largest untapped high-grade iron ore deposits in the world. Simandou’s iron has been coveted by the largest international mining companies for decades, but complicated operational logistics, combined with extreme political instability, corruption allegations, and legal disputes, have made this a challenging feat to achieve.

The northern half of the mining area, Block 1 and 2, is owned by Winning Consortium Simandou (WCS), led by Singapore-based Winning International Group.

The southern part of the mining area project – Block 3 and 4 – is owned by Simfer, led by Anglo-Australian mining company Rio Tinto, which acquired rights to Simandou in 1997.

In August 2022, WCS and Rio Tinto Simfer agreed to start the construction of a 650 km railway, a deep-water port, and other infrastructure needed to support mining operations. Recent reports set the completion of the railway by end of 2025, and the first ore shipments by November 2025.

Impact on human rights and communities

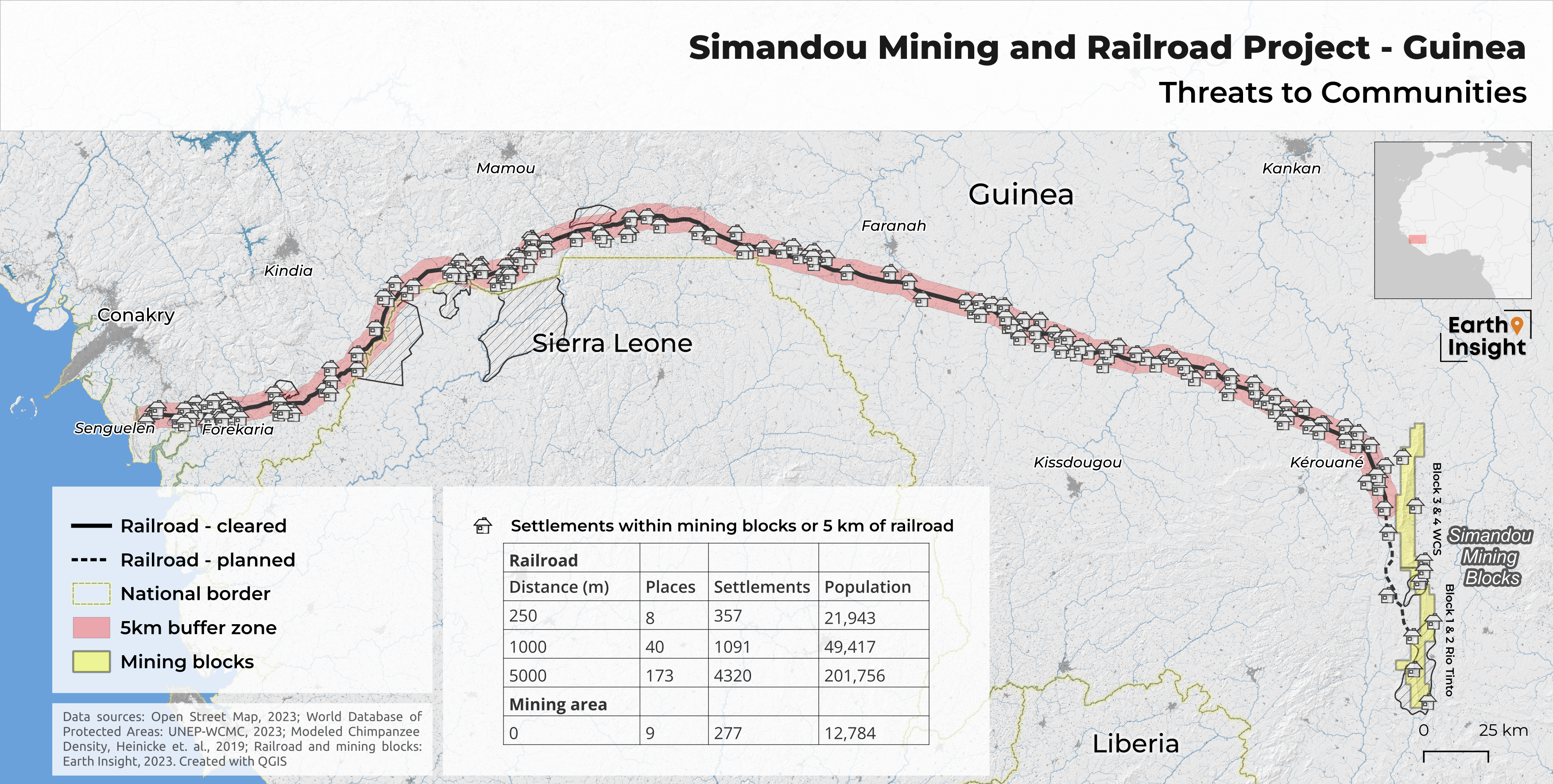

Land acquisition and displacement Hundreds of people have been displaced during construction of this project. Local communities, especially women, have been evicted without proper consultation to make space for Winning Consortium Simandou (WCS)'s living quarters in Block 1 and 2. In addition, the railway passes through a territory that is home to at least 450 communities. Several impacted community members have expressed concerns about the obstacles they face in negotiating equitable compensation, with many reporting under-compensation or outright theft of their homes and agricultural lands. Article One’s 2024 human rights report, commissioned by SimFer, highlights how the current cash compensation endangers financial security as it can be spent on items with lower economic return, rather than replacement land.

Impacts on livelihoods WCS' environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) (1) warns that deforestation and land loss associated with the construction risk impacting activities that are critical for communities’ food security. Coastal communities living near the Simandou port have denounced the complete devastation of their livelihoods, as port construction and vehicle traffic have driven away fish populations and blocked access to productive fishing grounds. Communities in Blocks 1 and 2 have also been heavily impacted, as noise pollution from machinery has driven away usual wildlife, creating scarce hunting conditions. These communities have also reported decreased agricultural yields from the dumping of the project’s laterite soil and mud near cultivation areas. Further, dust inhaled from the site threatens health, especially for children, the elderly, and the infirm. Article One’s report also lists further impacts arising from project-induced migration, whereby an influx to the project area has created a shortage of accommodation and increased healthcare and education costs.

Ineffective accountability mechanisms WCS’s grievance mechanism has delivered poor outcomes. Of 29 cases supported by Action Mines Guinée between August 2023 and September 2024, none were resolved on time, 8 were rejected, 6 under-compensated, and 11 still under review. Article One's assessment of SimFer’s process also found low community awareness and limited resolution of complaints.

Impacts on civic space Guinea's civic space, including threats to freedom of association and expression, is classified as “repressed” in the CIVICUS 2024 assessment. Rights-holders at the local and national levels may risk reprisals when seeking to denounce violations of their rights.

Impacts on cultural rights The railway has the potential to impact over 100 cultural and spiritual sites, like sacred sites, graves, and cemeteries. According to Simfer’s 2024 ESIA, the conglomerate has set up a Cultural Heritage Management Plan to manage cultural sites found in the project area. This plan includes avoiding the sites wherever possible, and if not, consulting communities on relocation or compensation. However, Article One’s assessment relays concerns by rightsholders on the pace of compensation. The report also stresses the ongoing impacts in the Pic de Fon Forest mining zone, including the destruction of burial sites.

Unsafe working conditions and fatalities Since June 2023, 13 workers have died during port and railway construction; none publicly reported. These unusually high fatalities raise concerns that safety is being sidelined, after Rio Tinto’s push to bring forward iron ore production from 2026 to late 2025. Reuters reviewed reports of over 40 undisclosed accidents. Both companies' officials and a safety audit by French firm Artelia cited poor safety and health conditions. In 10 cases, families of the dead or injured signed waivers exempting WCS from liability, an uncommon practice in industrial settings.

Impact on climate

Carbon emissions The Simandou iron ore mine has the potential to generate significant carbon emissions, including during land and forest clearing, drilling, blasting, hauling, and processing. WCS’s own environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) estimated that Blocks 1 and 2 alone have the potential to produce up to 19 million tonnes of carbon emissions over the 26-year anticipated lifetime of the mine, which is equal to about 41% of Guinea’s total emissions in 2020 and equivalent to burning 10 million tonnes of coal. An independent expert evaluated the company’s ESIA, and concluded that this is “likely a gross underestimate”, because of a failure to include emissions resulting from deforestation. On top of this, the land clearing alone - also as estimated by WCS - could release up to 271,300 tonnes of carbon dioxide, which, according to an analysis by Human Rights Watch, is equivalent to burning about 136,000 tonnes of coal. Beyond the environmental impact of the project construction fuel use, Rio Tinto Simfer’s ESIA report estimates that 94.7% of the emissions will come from the actual operation of the mine (mining, ore handling, and rail and port operation).

Not only will the project lead to significant deforestation, but according to WCS’s ESIA, the energy needed to power the mining operations will be generated with a Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) power plant, a major source of carbon emissions and other toxic byproducts.

Additionally, the railway that will connect the Simandou mine with the coastal port will utilize diesel-fueled locomotives, which emit high levels of nitrogen dioxide. Nitrogen dioxide is 240 times more destructive to the ozone layer than carbon dioxide, posing a significant risk to air pollution, health issues and environmental damage.

Insufficiently "green" steel Project proponents have claimed that the high purity of Simandou’s iron ore will facilitate the production of "green steel," using carbon-neutral methods like direct reduced iron (DRI) processes that rely on hydrogen instead of coal. However, this claim is largely unfounded. In order to be used in DRI processes, the ore should have an iron content of 67% or greater. Of the 1.5 billion tonnes of the proven iron ore reserves in Simandou, only 18% has an iron content of 66.5%, the remaining 82% has an even lower iron content of 65%. Thereby, the vast majority of Simandou’s iron ore is likely not pure enough for DRI processes. Regardless, Rio Tinto still plans to sell the iron ore for traditional coal-fired blast furnace use. Moreover, China Baowu group, the one confirmed steel maker who will use Simandou iron ore, does not have any green hydrogen DRI projects in the pipeline. Its one DRI plant uses fossil gas as a reducing agent, meaning Simandou iron ore will not be used for fossil free steelmaking.

Any potential climate benefit of the project comes at a high local environmental cost as residents of Diala and Diarakendou report solid waste pollution from construction, which the companies have not addressed.

Impact on nature and environment

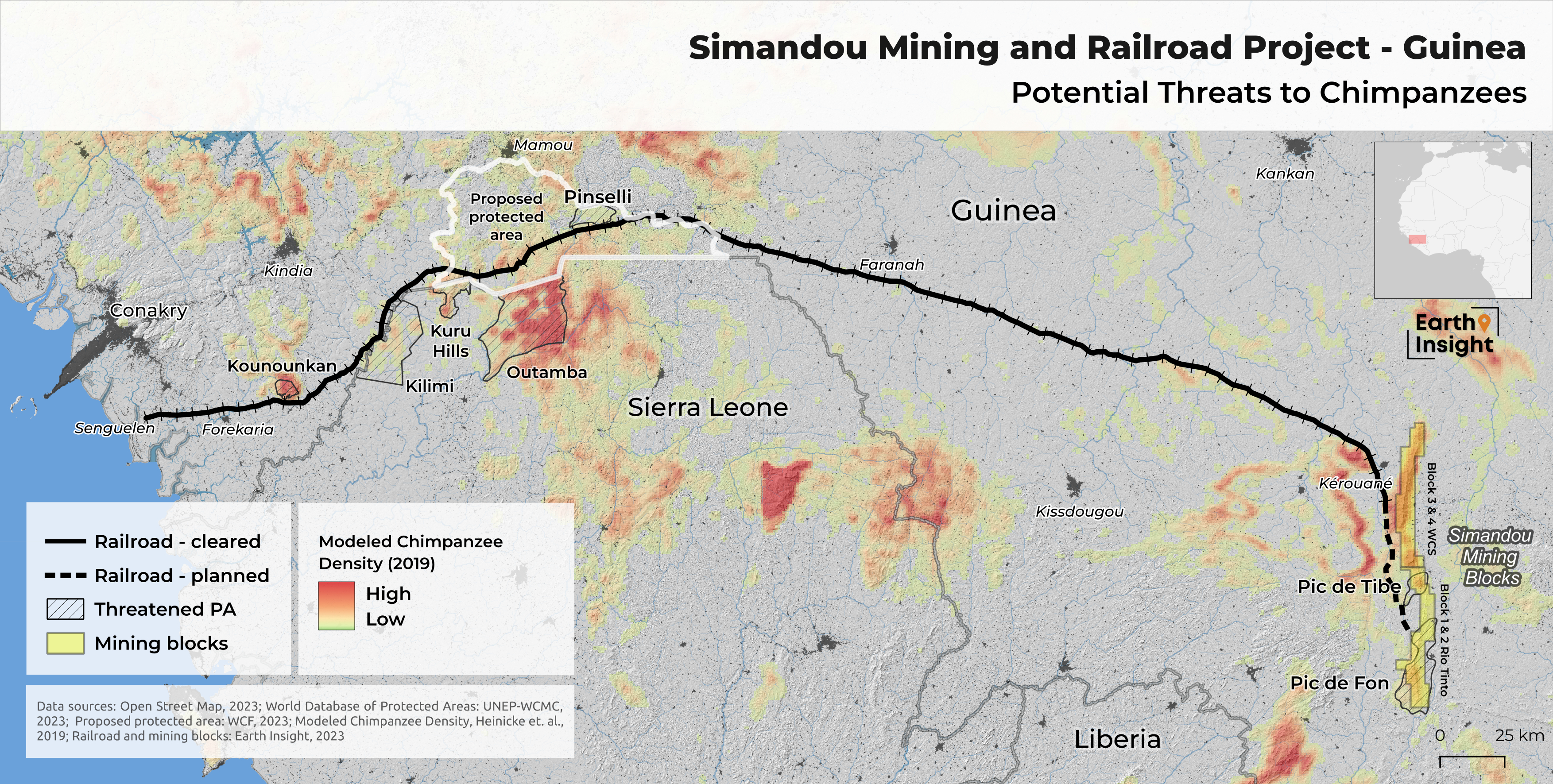

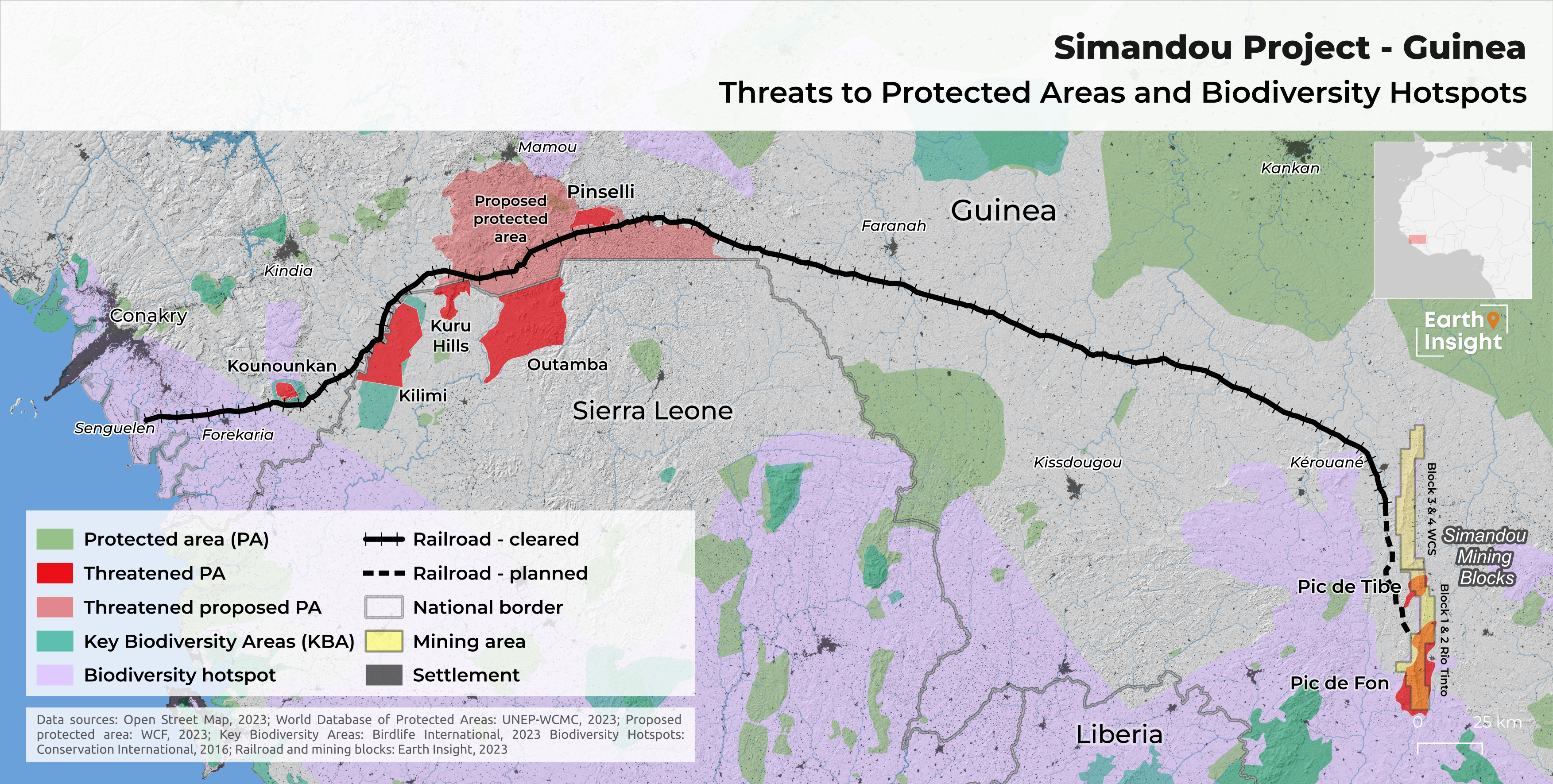

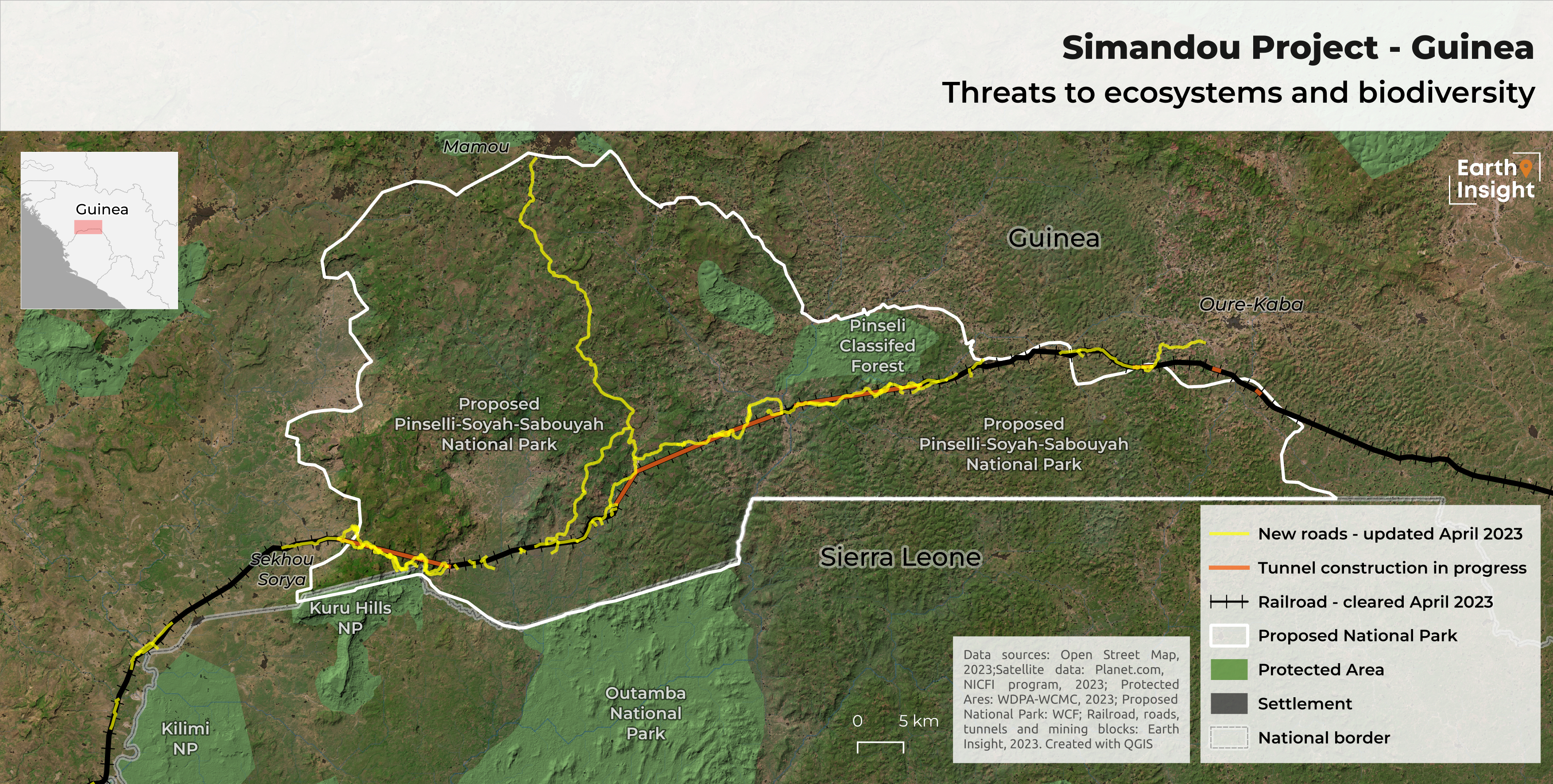

Impacts on biodiversity and wildlife Guinea has been facing rapid rates of deforestation, with the Nzérékoré region – where the Simandou project is located – having experienced the highest rate of deforestation in the country between 2002 and 2024. The clearance of large areas of forest for mining can lead to habitat loss and fragmentation, disrupting ecosystems and affecting biodiversity. The Simandou region is home to a diverse range of wildlife, including endangered and endemic species. The loss of habitat can lead to a decline in these populations, which can have long-term ecological consequences. Winning Consortium Simandou (WCS)’s activities have already put nature into great danger, as the company has already cleared approximately 85% of land necessary for the construction of the railway, according to an analysis by Earth InSight. The railway’s route cuts through extensive tracts of primary rainforest known to be the natural habitat of the critically endangered Western Chimpanzee and African Forest Elephant and the endangered Western Red Colobus monkey.

There are clear indications that the impacts of the railroad construction extends well beyond what was presented in the ESIA. A 2022 review of WCS’s environmental and social impact assessment revealed that the company failed to assess its mining blocks for these well-known endangered species, and that its plans to mitigate impacts on biodiversity were grossly inadequate.

Impacts on protected nature areas The railway traverses several protected areas, including the Haut Niger National Park, which was created to protect one of the last remnants of dry forest in Guinea, and the Outumba-Kilimi-Kuru Hills-Pinselli-Soya Transboundary Priority Landscape, which includes primary forest, buffer zones, and corridors essential for the survival of endangered species such as the forest elephant, pygmy hippopotamus, and the Western African chimpanzee. The railway will run just adjacent to other protected areas, such as the Outumba-Kilimi National Park in Sierra Leone and Kounounkan Classified Forest, likely opening these previously isolated areas up to inward migration and exploitation for bushmeat and forest clearance.

Simfer’s mining zone includes the Pic de Fon Classified Forest, which is home to critical chimpanzee populations; while Simfer acknowledges that it plans to mine in the Pic de Fon, it has declined to include the area in its current environmental and social impact assessment and has instead indicated the need for a supplementary assessment before operations begin in the forest.

Impacts on water sources The railway currently being developed cuts across several important waterways, and communities have already reported that critical water streams have been polluted due to construction activity. Reported cases include the pollution of watercourses by pipeline water at the Sekoussoriyah tunnel (Kindia region), pollution of the Balin stream at Oure Kaba (Mamou region), pollution of springs (Warada and Namba) by drilling work at Damaro (Kérouané region), and drainage of mud and sand into the Karako-Konsankoro stream bed (Kérouané region). Additionally, the Simandou mining project will release heavy metals, posing a threat to the health of nearby communities and endangering aquatic ecosystems. According to the project's environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA), there is a high probability that toxic effluents will be produced near the region's major rivers, notably the Dion, Milo and Diani. Pollution of water sources – as explained by a 2022 assessment of the WCS’s ESIAenvironmental and social impact assessment – could have devastating impacts, as the mining blocks cover over 100 km of mountains whose streams feed directly into the water of the Niger River, Africa’s third longest river and a critical water source across four West African countries. Simfer’s own ESIA notes that its operations will cause major, long-term reductions on ground and surface water sources in the area that cannot be adequately mitigated. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis of the project’s impacts on water is necessary before it goes ahead.

Impact on pandemics

Emergence of new infectious diseases Several studies suggest that large-scale industrial development projects, such as mining, can increase the risk of zoonotic disease transmission, which can lead to pandemics. A recent report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) emphasises the importance of protecting biodiversity and natural ecosystems in preventing future pandemics. The report notes that the destruction of natural habitats, including deforestation, which often takes place in mining operations and is a risk associated with the Simandou project, can increase the likelihood of zoonotic disease transmission. Furthermore, the railway associated with the Simandou project cuts across an area that was the epicentre of the West Africa Ebola outbreak, which killed over 11,000 people between 2013-2016. This shows the concrete risks of pandemics and other widespread disease outbreaks in this area in Guinea.

Other impacts

Links to impacts at Boké bauxite mine WCS was set up by the same founders as the SMB Winning Consortium, a mining group that exploits the Boké bauxite mine in northwestern Guinea. This consortium has a disastrous track record of unremediated human rights impacts and disrespect of community land and environmental rights, as documented extensively in a 2018 Human Rights Watch report and a 2023 Natural Justice community audit. The pattern of negligence with respect to air quality, uncompensated or undercompensated taking of lands, and pollution of water sources already observed along the Simandou railway route - along with the lack of transparency and hesitation to engage substantively with affected communities - is strikingly similar to the criticisms of SMB’s record at Boké.

Lawsuits Several communities and individuals have filed grievances with WCS and Simfer, asking for resolution of complaints related to water contamination, land loss, improper compensation, damage to homes, and livelihoods impacts. Most of these complaints are still pending. In addition, a group of affected communities filed a petition in July 2024, requesting the suspension of WCS’s environmental clearance certificate due to WCS’s deplorable environmental record, its failure to properly consult local populations, and its violation of various international obligations of the Republic of Guinea, including climate change and biodiversity commitments and fundamental principles of international environmental law such as the precautionary principle.

The total costs of the Simandou project are reported at US$ 24 billion. The two main project sponsors are Singapore-based Winning International Group, the majority shareholder of the Winning Consortium Simandou (WCS), developing Blocks 1 & 2 in the north; and Anglo-Australian mining company Rio Tinto, which is leading the Simfer consortium, developing Blocks 3 & 4 in the south. Simfer has committed US$ 11.6 billion of this funding, and Rio Tinto’s share within this consortium amounts to US$ 6.2 billion.

Commercial banks finance Rio Tinto via loans, bonds, and shareholdings. See more information on our Rio Tinto Dodgy Deal Profile here.

Commercial banks have also financed Winning International Group, a privately held company, via loans. DZ Bank, BNP Paribas, Credit Suisse, and Standard Chartered all provided loans to Winning International Group in the years between 2018 and 2022 (Profundo finance research, June 2023).

In addition, China Baowu Steel Group, which is part owner of Simfer and also owns a 49% stake in WCS’s mine and infrastructure operations, raised US$ 1.4 billion from a bond issue, in part for the Simandou project.

Block 1 and 2 of the Simandou project are owned by the Winning Consortium Simandou (WCS), which is owned by Singapore-based Winning International Group (45%), China's Hongqiao Group (35%) and Guinea's United Mining Suppliers (15%).

Blocks 3 and 4 are owned by Simfer, which is jointly owned by Australian mining company Rio Tinto (53%) and Chinese Chalco (47%). Chalco is in turn owned by a consortium of Chinese state-owned enterprises, most notably Chinalco and Baowu, the world’s largest aluminum and steel companies respectively.

Applicable norms and standards

Simandou Project: conservation view

Source: EarthInsight. See additional maps from EarthInsight's rapid assessment of threats to Conservation, Biodiversity and Communities in the Impacts section above.