Project – Active

This profile is actively maintainedUlinzi Africa Foundation (UAF)

Project – Active

This profile is actively maintainedUlinzi Africa Foundation (UAF)

Why this profile?

Base Titanium is prospecting to mine in an area that is globally recognised as a biodiversity hotspot, home to endangered species such as sea turtles, elephants, dugongs, lions, and the endemic Coastal Topi, found nowhere else on earth. It also hosts critical habitats, including mangroves, Important Bird Areas, and wildlife and avian migratory corridors. Any mining activity here poses serious risks to ecosystems, biodiversity, climate resilience, and local livelihoods, particularly for communities dependent on fishing, farming, and pastoralism. The project also raises legal and governance concerns, as it appears to bypass critical safeguards such as Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEAs) and Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs).

What must happen

The government should not permit this mining activity. Base Titanium should stop compromising people and abusing elected officials offices for their financial gain. The global community should decry this activity and stand with communities and environmental defenders to save the home of our coastal elephants. Banks should avoid direct or indirect exposure to this project at all costs.

| Sectors | Mining , Nonmetallic Mineral Mining and Quarrying |

| Location |

|

| Status |

Planning

Design

Agreement

Construction

Operation

Closure

Decommission

|

Base Titanium has submitted several prospecting applications in Tana River and Lamu Counties in Kenya to explore for titanium and the heavy minerals ilmenite, rutile, and zircon. (See the Updates section below for specific application numbers.) The company's licensing blocks have since been passed to two organisations named Celestlink Investments and Kenarife Resources, about which nothing is yet known.

Impact on human rights and communities

Food Sovereignty and Livelihoods: Mining operations in the proposed area pose significant risks to the human rights of local fishing communities, including their right to food sovereignty and sustainable livelihoods. Pollutants such as titanium oxide (TiO2) in marine ecosystems could contaminate food sources, adversely impacting marine life and exposing humans to health risks through consumption (Frontiers, 2024). The failure to investigate these risks disregards the community’s right to health and safety, undermining their ability to sustain themselves and protect their traditional way of life.

It has been documented that many displaced community members and farmers have been adversely affected by Base Titanium mining operations in Msambweni, further aggravating livelihoods.

Right to Health: The mining process exposes nearby communities to respirable Elongated Mineral Particles (EMPs) and rutile dust, which the World Health Organisation associates with severe health outcomes, including systemic inflammation, respiratory diseases, and cardiac issues. These health threats disproportionately affect marginalised communities with limited access to healthcare, violating their right to health. Furthermore, the economic burden of ill-health deepens poverty, exacerbating inequalities and violating commitments to uphold Sustainable Development Goals on health and well-being, and eliminating poverty. The failure to address these risks prioritises profits over the fundamental rights of vulnerable populations.

Threats to Wildlife and Human-Wildlife Conflict: Increased noise, traffic, and land vibrations disrupt wildlife behaviour, leading to territorial displacement and an escalation of Human-Wildlife Conflict. Displacement also risks disease transmission between wildlife and humans, posing further threats to the health and safety of nearby communities. These impacts constitute a violation of the community’s right to a safe and sustainable environment, critical for their well-being and livelihoods.

Cultural Heritage and Identity: The proposed mining area includes irreplaceable cultural heritage sites, such as the Ungwana Bay Ruins and the Old Sultan's Palace, dating back to 1200 AD. Destroying these sites erases the cultural identity of Indigenous communities, violating their right to cultural heritage and self-determination (see 4.5.2 - Social and cultural values). The influx of external workers risks eroding cultural norms and values, further marginalising these communities. Documented cases of prostitution and sexually transmitted diseases at other mining sites highlight the risks to public health and social cohesion, compounding the violations.

Displacement and Dispossession: Any forced displacement for the project would violate the community’s rights to land, housing, and livelihood security. The transfer of land to the government after the project would disregard the community’s long-term rights to ownership and self-determination, amounting to a strategic and systematic disempowerment of vulnerable populations.

These cumulative impacts represent serious human rights violations, undermining the dignity, health, culture, and livelihoods of the affected communities.

Impact on climate

Kenya’s forests, long undervalued for their critical ecological functions, face escalating threats from deforestation and now potential mining. These ecosystems are indispensable for regulating climate, supporting biodiversity, providing clean water, and sustaining indigenous cultures. With Kenya enduring severe droughts, protecting forests is vital for climate resilience. Globally, forests could mitigate between 4.1 and 6.5 GtCO2e annually by 2030, underscoring their importance in combating climate change.

Mining and associated infrastructure, such as roads and power lines, exacerbate habitat fragmentation and biodiversity loss. These developments increase accessibility, driving hunting, logging, artisanal mining, charcoal extraction, and small-scale agriculture—all direct threats to ecosystems and climate resilience.

The proposed prospecting area is a crucial carbon sink, hosting intact forests and Mangrove Forests, including eight of the nine species found in Kenya, such as Avicennia marina and Rhizophora mucronata. These ecosystems stabilize carbon storage, absorb a quarter of global anthropogenic carbon emissions, and regulate hydrological regimes, generating rainfall and strengthening drought resilience across the landscape.

Intact Forest Landscapes (IFLs) in the area are home to endangered and endemic trees like Euphorbia tanaensis and Triclulia emetia, as well as medicinal plants. Mineral-sand mining would result in the direct loss of these critical species, further endangering biodiversity and undermining ecosystem health.

The destruction of these forests would also threaten the region's capacity to adapt to climate change, impacting local and global efforts toward resilience. Given these critical ecological and climatic roles, granting mining licences in such ecosystems would result in irreparable damage, undermining Kenya’s environmental and climate goals.

Protecting these forests is not only essential for biodiversity and local livelihoods but also for ensuring Kenya's broader climate resilience and global ecological responsibility.

Impact on nature and environment

The proposed prospecting area in Kenya falls within a Key Biodiversity Area (KBA), a globally recognised site critical to the persistence of biodiversity. This marine-sensitive zone includes beaches where all five endangered sea turtle species nest, Important Marine Turtle Areas, shark and ray nurseries, and breeding grounds for finfish, molluscs, and crustaceans—vital to local livelihoods and economies. Additionally, the area is an Important Bird Area (IBA), supporting endemic and endangered bird species, and serves as a stopover along the Eurasian Flyway, essential for migratory birds.

The site encompasses an Environmentally Sensitive Area (ESA) under Kenya's Environmental Management and Co-ordination Act, 1999. It contains giraffe migratory corridors and an elephant corridor linking the Coastal and Tsavo landscapes, vital for mitigating human-wildlife conflict and preserving genetic health. The location also borders a Ramsar wetland site of international importance and a proposed UNESCO World Heritage Site, hosting diverse frog species, key bioindicators sensitive to pollution (see UAF map).

The area is a stronghold for the endangered Coastal Topi, a species endemic to Kenya. The loss of this ungulate would disrupt seed dispersal, prey availability, and overall ecosystem health. Additionally, it supports lion prides, including the first collared lion on East Africa’s coast. Removing these apex predators could trigger a trophic cascade, destabilising the ecosystem.

Despite these ecological values, no Species Environmental Assessment Guidelines (SEAGs) exist, and baseline studies for critical species, like frogs, remain absent. An Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is essential to evaluate and mitigate potential threats. The national government must uphold its obligations under the Ramsar Convention and prioritise the preservation of this biodiverse region. Moving forward with prospecting risks irreparable harm to endangered species, ecosystems, and the communities relying on them. Protecting this area is imperative for Kenya’s natural heritage and global biodiversity.

Other impacts

The proposed mining project poses severe risks of human rights violations by undermining Kenya’s Constitution (2010), which guarantees its citizens the right to a clean and healthy environment (Article 42). Mining activities threaten present and future generations' rights by causing environmental degradation, contrary to the Constitution's mandate for environmental protection. The lack of transparency, accountability, and public participation in such projects violates Article 10, which underscores national governance principles.

Key legislations like the Water Act, 2002 and the Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA) prohibit activities harmful to protected areas, ecosystems, and water reserves. Mining, being water-intensive, risks depleting vital water sources, disrupting ecological functions, and violating these protections. Additionally, the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act (2013), which ensures the sustainable use of wildlife, is undermined by the presence of extractive industries in wildlife-sensitive areas.

Cultural and historical rights are also at stake. The National Museums and Heritage Act (2006) protects sites of cultural significance, several of which lie within the proposed mining area. Destruction of these sites would erase local heritage, violating communities' rights to cultural preservation and identity.

At an international level, Kenya is bound by treaties that recognise environmental protection as a human right. The Rio Declaration and the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirm that a healthy environment is integral to human well-being. The Ramsar Convention obligates Kenya to conserve wetlands like the Tana Delta, a designated Ramsar site, yet the project threatens its ecological character.

Kenya’s commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Kunming-Montreal Agreement, including the "30 by 30" initiative, are at risk. Mining activities in sensitive ecosystems undermine these global goals, alongside national obligations under Kenya’s Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan.

The project also contradicts Kenya’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, which aim to mitigate climate change. By degrading forests and ecosystems, mining hampers climate resilience and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on climate action (SDG 13), life below water (SDG 14), and life on land (SDG 15).

The cumulative impacts represent violations of environmental, cultural, and socio-economic rights, eroding global and national human rights obligations.

Base Titanium’s plans to finance its mining plans in Lamu and Tana River counties are not yet known. According to one media report, it may take the company between five and 10 years to establish the existence of adequate resources before making a significant investment. Less information is available now that the blocks have been passed to the two new companies Celestlink Investments and Kenarife Resources.

The commercial banks that provided a loan for Base Resources’ other Kenyan mining project, the Kwale project, are CAT Finance, NedBank, Standard Bank, and Portigon Financial Services. In addition, development institutions DEG, FMO and Proparco also provided a loan for the Kwale project.

The company’s Annual Report 2024 (p80) lists its main shareholders. The largest are Pacific Road Capital Management GP II Ltd, registered in the Cayman Islands (23.27%), HSBC Custody Nominees Limited (22.79%), JPMorgan Nominees Australia Pty Limited (11.36%) and Citicorp Nominees Pty Limited (11.35%). The accounts linked to commercial banks are likely to represent nominee shareholdings managed by the bank on behalf of an unknown beneficial owner.

Project sponsor

Base Resources

AustraliaOther companies

Celestlink Investments

- international -Kenarife Resources Investment Co. Ltd.

- international -Applicable norms and standards

2025

2025-11-27 00:00:00 | Update November 2025

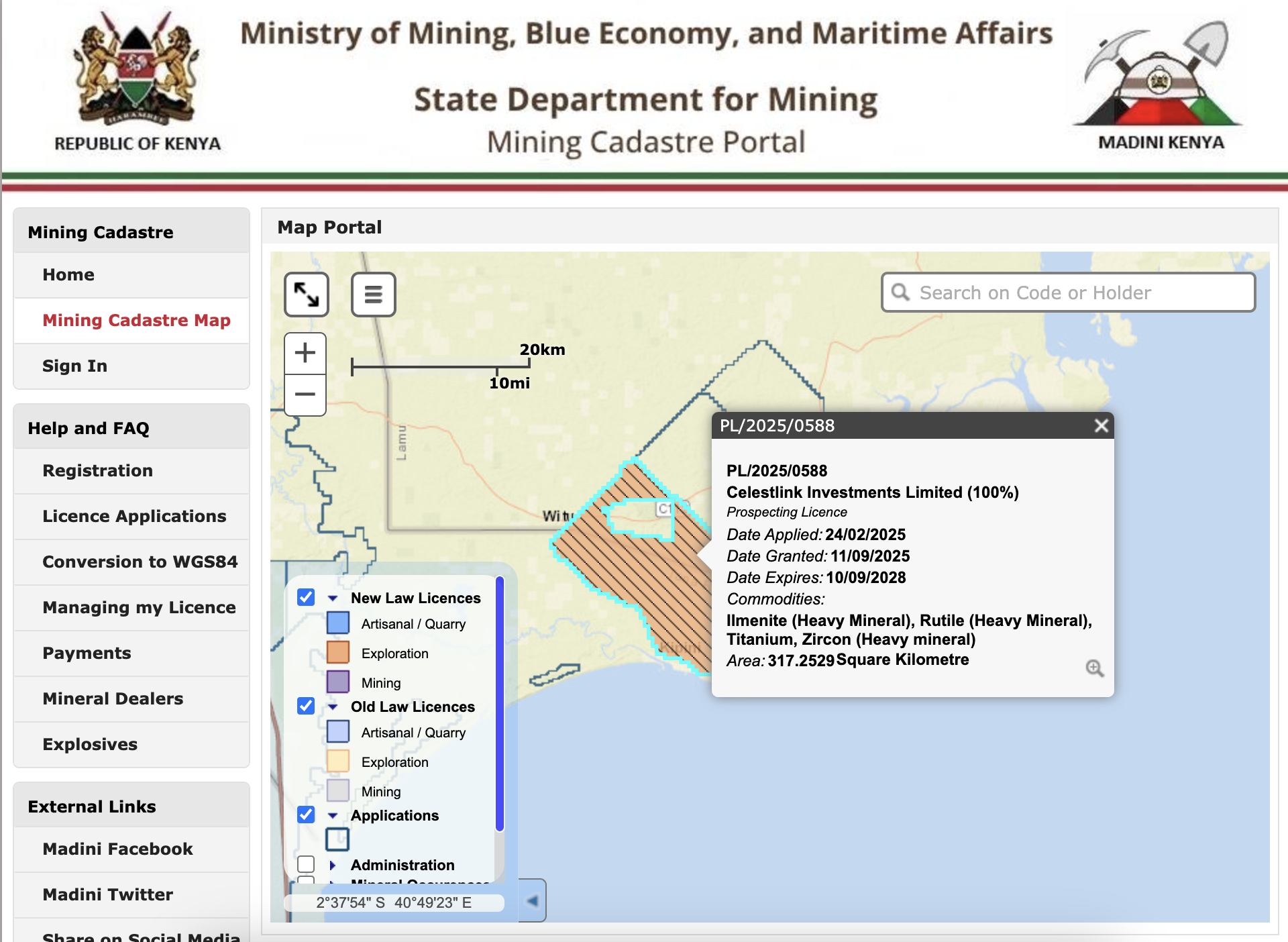

The prospecting licence for Block PL/2025/0588, now held by Celestlink Investments Limited, was granted on 11/09/2025, according to the Mining Cadastre Portal.

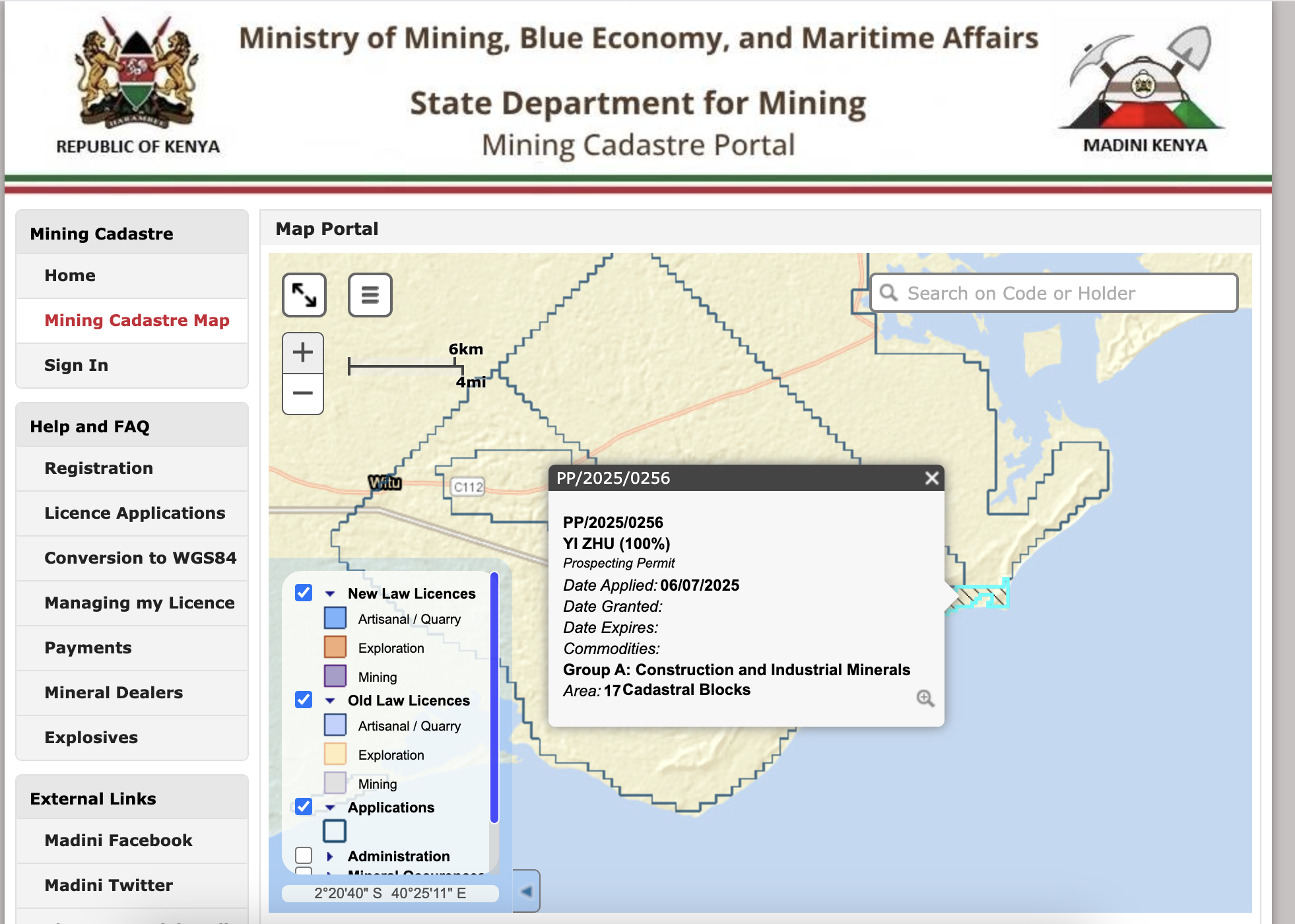

In September, the block PP/2025/0256 was transferred from Kenarife Resources Investment to Yi Zhu, also according to the Cadastre. See the screenshots below.

2025-07-29 00:00:00 | Celestlink Investment linked to Kenyan mining secretary

Whistleblower Nelson Amenya alleges that Celestlink Investment, the company that now owns several of the mining blocks in Lamu and Tana River, is owned by Kenya's Cabinet Secretary for Mining, Hassan Joho, via a proxy. The allegations were covered by Kenya Insights as part of a story about the alleged sale of the Kipini Conservancy.

2025-03-28 00:00:00 | Project blocks taken up by Celestlink and Kenarife Resources

The same blocks have now been taken up by two companies and fragmented into 3 primary blocks and 4 micro-blocks as follows:

APP No/6522 dated 26/02/2025 Celestlink Investments (same block as Base Titaniums PL 2019/0266)

APP No/6521 dated 26/02/2025 Celestlink Investments (same block as Base Titaniums PL 2019/0265)

APP No/6511 dated 24/02/2025 Celestlink Investments (same block as Base Titaniums PL 2019/0263) (without exclusion zone covering Witu National Forest Reserve)

Micro-blocks:

APP No/6520 dated 26/02/2025 Kenarife Resources Investment Co. Ltd. (Within former 0265 current 6521)

APP No/6519 dated 26/02/2025 Kenarife Resources Investment Co. Ltd. (Within former 0265 current 6521)

APP NO/6514 dated 26/02/2025 Kenarife Resources Investment Co. Ltd. (Within former 0265 and 0266 current 6521 and 6522)

APP No/6517 dated 26/02/2025 Kenarife Resources Investment Co. Ltd. (Within former 0266 current 6522)

2025-01-30 00:00:00 | Project history

Base Titanium filed applications for licences to prospect for minerals in Lamu and Tana River counties on 19/09/2019 (PL 0263), 24/09/2019 (PL 0265) and 03/10/2019 (PL 0266)

In June 2024, following gazette notices published on 24/05/2024 (No. 6282 and 8283), Ulinzi Africa Foundation filed an objection to the proposed mining prospecting blocks PL/2019/0265 and PL/2019/0266.

On 15/11/2024 a publication appeared in the Kenya Gazette (Number CXXVI 197) on PL 2019/0263.

On 24/11/2024, a notice signed off by the Cabinet Secretary appeared in newspapers separately, indicating an entirely different licence application, notably PL/2023/0306. On checking the coordinates provided in this notice, they were directly concurrent to the block under application PL/2019/0263.

In December 2024, a coalition of some 29 civil society organisations sent a petition to the mining Cabinet Secretary, objecting to the project. Community members also filed responses via a legal firm, in response to the notices.